Randy Boswell, Chris Mikula, The Ottawa Citizen (Dec. 7, 00)

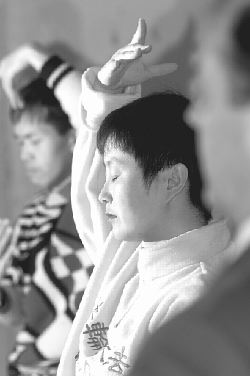

Lucy Zhou practises Falun Gong at the Chinese Community Centre in Ottawa, yesterday.

KunLun Zhang, a 60-year-old Canadian citizen formerly from Montreal, has been sentenced to three years in a forced-labour camp in China for performing Falun Gong exercises in a public park. Chinese President Jiang Zemin made a gross miscalculation by banning Falun Gong in July 1999, instantly transforming a politically innocuous meditation movement into a genuine threat to the Communist regime's stranglehold on China, a new book by an American writer says.

The brutal crackdown was expected to wipe out the movement within a few weeks. But by tapping a new spiritual hunger among well-educated Chinese professionals and transplanting itself globally via the Internet, Falun Gong avoided the fate of other banned activities and -- almost by accident -- galvanized millions of people in China and around the world in opposition to Beijing's oppressive policies.

In Falun Gong's Challenge to China, New York author Danny Schechter first recounts the unremarkable origins of Falun Gong in the early 1990s as one of many modern Qigong practices derived from Buddhist teachings and rooted in traditional Chinese medicine. Then, in tracing Falun Gong's rising popularity in the late 1990s, he identifies the fateful series of events last year that prompted China's government to launch its propaganda war and police-state persecution against practitioners. The campaign appears destined to backfire at home and on the international stage.

The issue is now drawing attention in this country because KunLun Zhang, a 60-year-old Canadian citizen formerly from Montreal, has been sentenced to three years in a forced labour camp in China for performing Falun Gong exercises in a public park. His daughter LingDi, a University of Ottawa student, has appealed to the Canadian government for help, but China has refused requests by Foreign Affairs officials in Beijing to visit Mr. Zhang. Meanwhile, there's a rising chorus of opposition to the Falun Gong crackdown from human rights organizations around the world and signs that some countries -- such as Britain -- are prepared to push again for a United Nations resolution criticizing China's human rights record. "China was completely unprepared for this," says Mr. Schechter, author of several books on human rights and an Emmy award-winning broadcaster. "This whole resistance thing has spread globally. Falun Gong doesn't really have a political character in the normal sense, but as China pushes them China is politicizing them."

Mr. Schechter, who describes himself as a "skeptic" toward claims by some practitioners that Falun Gong has helped heal their physical ailments, says the meditation exercises and simple lessons for living promoted by Falun Gong founder Li Hongzhi -- chiefly adherence to the principles of "truth, compassion and forebearance" -- "are no more perplexing than many supernatural belief systems and New Age-type practices in the United States." But what makes the story of Falun Gong unique in China's history, argues Mr. Schechter, is the speed with which its popularity has grown and the timing of that phenomenon. The emergence of Falun Gong coincided with the rise of the Internet -- an instant means of communicating over vast distances -- and a new demand for spiritual rootedness in an era of social upheaval. "This thing starts in 1992 -- relatively recently -- and Li Hongzhi teaches it personally himself for only two and a half years," says Mr. Schechter. "And then the thing spreads dramatically in China to the point where government studies estimate that between 75 and 100 million people are involved. Many of the people who get involved are people in the party structures, including the wives of ministers. So the thing is very, very popular.

"At the same time there's a major transformation under way in China from a rigid, state-controlled, party-dominated culture to a more market-driven, open economy and society," he adds. "The party and the old apparatus is trying to maintain its control in this emerging capitalist arena. And this has created a number of stresses, including fear and hostility on the part of the government to the democratization of China."

Mr. Schechter says "there's a lot of irony in this" campaign against Falun Gong because its practitioners were "not against the government in China, they were not even criticizing the government." Unlike the pro-democracy protesters whose movement was violently crushed at Tiananmen Square in 1989, and the underground groups that continue that fight today, Mr. Schechter says people practising Falun Gong are focused on self-improvement rather that broad social change, personal growth rather than politics.

But in April 1999, according to Mr. Schechter, a single derogatory article about Falun Gong in a state-sponsored magazine for teenagers sparked the bitter conflict that now grips Chinese society. In the article, scientist He Zuoxiu gave voice to the view among many party officials that Falun Gong and other meditation practices represented a reversion to superstitious beliefs that ran counter to Communist doctrine. The response was a demonstration by several thousand Falun Gong practitioners outside the magazine's offices in the city of Tianjin, which turned bloody when riot police beat the demonstrators and arrested 45. That led to a larger protest in Beijing on April 25, 1999, during which an estimated 15,000 Falun Gong supporters gathered for a peaceful "appeal" for a formal retraction of the derogatory message about their practice.

"Nobody had ever seen anything like this before," says Mr. Schechter. "But these people are not like the Tiananmen Square protesters: they're not kids, they're not carrying any placards, there's no posters, no slogans, no songs. They're standing stoically, reading books. It's not political. It's simply an appeal against this grievance." Nevertheless, the size of the crowd made a strong impression on Mr. Jiang, the Chinese president. At the same time, says Mr. Schechter, leaders of other Qigong practices were complaining to Beijing that Li Hongzhi's policy of offering free Falun Gong sessions -- while limiting profits to sales of books outlining the principles of the practice - was undercutting their business. "So they ban this thing," says Mr. Schechter. "And everybody figures it's over because the government is very powerful, the army, police, you know. But guess what? For over a year and a half now, there's been resistance of a kind they've never seen before in the 50-year history of the People's Republic of China. There's never been anything like this kind of non-violent resistance in the heart of Beijing and 30 other cities in the country, persisting over months. The thing they didn't anticipate was that Falun Gong had gone global."

From dozen outposts around the world -- including Ottawa -- where Falun Gong is practiced by immigrants from China and a growing number of non-Chinese participants, resistance within China is being fostered and maintained despite the deaths of close to 100 people and the imprisonment of tens of thousands of others.

Falun Gong practitioners within China "now realize there are some things called human rights, which they never would have asserted before, and that those human rights are being violated," says Mr. Schechter. "And a lot of the Chinese people being drawn to it overseas aren't the old ladies and retirees in tennis shoes. They're the young PhDs and chemists and scientists and engineers who are looking for some sort of spiritual dimension in their lives which connects them to their native country. So you have some of the best and the brightest of China drawn to this. The idea that this is a cult of wackos makes no sense," says Mr. Schechter. "Many of them are working for big corporations and what have you. You can't just demonize them."

Copyright 2001 Ottawa Citizen Group Inc.

http://www.ottawacitizen.com/national/001207/5004295.html

Category: Falun Dafa in the Media