(Minghui.org) There is a Chinese saying nowadays that goes like this: “The Party’s policy is like the moon; in two weeks, they'll sing a different tune.”

With policy that shifts at such speeds, it's hard to say whether the people who are favored by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will stay in such favorable positions in the long run. In fact, history has shown us that many of the CCP's darlings have often been scapegoated as soon as they have outlived their usefulness, and transformed into enemies of the state overnight.

Below are some examples.

The Ups and Downs of a “Red” Writer

Wei Wei, one of the most famous pro-CCP writers, wrote “Who Are the Most Beloved People?” in 1951 to praise the People's Volunteer Army in the Korean War. This article was included in literature across Chinese schools, making Wei a household name for a long time.

After the Cultural Revolution started in 1966, however, Wei became one of the first key people targeted within the military. He was attacked and humiliated in public at least 23 times.

Instead of learning his lesson, Wei and some other writers launched the left-wing publication Zhongliu (Midstream).

After former CCP leader Jiang Zemin proposed his “Three Represents” theory and included it in the Party constitution, the left-wingers within the CCP were unsatisfied with this policy. After Zhongliu published an article in July 2001 criticizing Jiang, the magazine was suspended the following month.

“It is hard to imagine that the author of ‘Who Are the Most Beloved People’ could now write an article called ‘Who Is the Most Deplorable Person’,” Jiang remarked. “To me, he is the most hated person.”

Wei was then placed under house arrest; his article “Who Are the Most Beloved People?” was removed from textbooks.

Wei Wei is a red writer who promoted the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Wei Wei is a red writer who promoted the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The heroes that Wei documented ended up in similar straits. Zhang Lichun was the inspiration behind Xiao Huzi, a key figure in “Who Are the Most Beloved People.” Although he was a veteran of eight battles, Zhang was quite miserable in his later years. When Wei met 81-year-old Zhang in 2005, he learned that Zhang had been framed by officials and ended up in jail for 5 years.

To make things worse, Zhang and his wife both lost their jobs. Their two sons could also not find work, and their youngest child, a daughter, had starved to death. To make a living, Zhang had been working as a street vendor repairing shoes for 30 years.

The stories of Wei and Zhang are only the tip of the iceberg, as far as CCP “heroes” go.

“It is so sad that the most beloved person had become the most pitiful person,” wrote one Chinese netizen.

“Most of the foot soldiers who joined the Korean War, the Indian War, and Vietnamese War ended up destitute and helpless at an old age,” another one added. “The Party treated them like rags, discarding them after use.”

Hero or Traitor?

Yingxiong Ernu (Heroic Sons and Daughters) was a classic CCP propaganda movie in China depicting the events of the Korean War. As such, it is far from the truth, but the main character dared not reveal this fact.

In the movie, the protagonist Wang fought against the United Nations forces until he was the last man standing. After yelling “To win the battle, fire the cannon at me!” into his walkie-talkie, he grabbed an explosive cartridge and jumped into a group of American soldiers, taking them with him as it exploded.

According to Jiang Qingquan, who Wang's character was based on, what he called out in the walkie-talkie was, “The enemy is now 50 yards from me, 30 yards, 10 yards! Fire the cannon at my bunker roof!”

But that was not the end of the story. As Chinese officials and media actively promoted the movie, they quickly found out Jiang did not die; rather, he had been held captive by the enemy and was on the list of returned prisoners of war. The United Nations forces had captured over 20,000 CCP soldiers. Most of them decided to go to Taiwan; only 6,670 decided to come back to mainland China, including Jiang.

Jiang and his comrades did not expect to face political trials right after their return. This is because the CCP did not acknowledge their captivity, instead labeling them as deserters. While Jiang received a warning sanction from the Party, others were not so lucky: 700 were expelled from the military, 4,600 were demoted to partial military status, and the majority of the 2,900 CCP members were expelled from the Party.

Jiang Qingquan, a hero with a background of “traitor”

Jiang Qingquan, a hero with a background of “traitor”

Jiang did not dare to mention this part of his experience to others, not even his wife and children. When he watched Yingxiong Ernu, he cried many times. His wife asked why, but he refused to answer.

“How could I bring this up during those years?” he recalled many years later, “if I talked about it and told others that I had been captured, I would have been dead.”

Nonetheless, keeping a low profile did not save him during the Cultural Revolution. Red Guards dug out the record of captivity from his file and labeled him a traitor. He was often attacked in public and forced to write self-criticisms. This did not end until 1981, five years after the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution.

From Literary Czar to Prisoner

Zhou Yang, former deputy minister of the Central Propaganda Ministry and the Culture Ministry, was probably the most powerful official of Chinese literature during 1950s and 1960s. Known as the literary czar, he followed Mao Zedong’s orders meticulously, and became the CCP's guard dog in the literary circle who attacked intellectuals that stepped out of line. For example, he launched campaigns against renowned writers Hu Feng and Ding Ling. Many people in the Writer's Association and officials within the Culture Ministry were his victims. Even his old friends, such as Xia Yan, Tian Han, and Yang Hansheng, were no exception to this excoriation.

Wei Junyi wrote in Si Tong Lu (Record of Recollection and Pain) that countless writers were felled because of Zhou: “It seemed he was the only correct one in the literary world.”

During a conference in 1979, someone asked Zhou how he could be so brutal when attacking others. He said when arresting these “rightist” intellectuals, Mao gave him a list—everyone on that list was a lamb for slaughter. Mao also ordered Zhou to give an update on the status of this persecution every day.

“Some people did not say anything against the Party. What should I do about them when there is no evidence?” Zhou asked.

“Let’s dig out the old materials from Yan’an!” Mao replied.

Although Zhou admired Mao very much and remained loyal to him, Mao still criticized him for “being too soft politically.” On July 1, 1966, Hong Qing (Red Flag) published an old article of Mao's with an editor’s note against Zhou.

A campaign targeting Zhou immediately began, leaving Zhou detained for nine years. At his hometown in Hunan Province, Zhou's son, who had died at a young age many years earlier, was dug out from his grave and had the remnants of his corpse scattered about.

“The person who had attacked others in the literary world was finally being attacked himself,” wrote Wei.

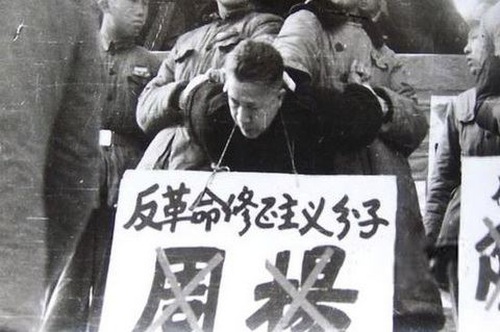

Zhou Yang, literary czar, was also attacked after he targeted others.

Zhou Yang, literary czar, was also attacked after he targeted others.

Lu Dingyi, former propaganda minister, once said, “In the past ten-some years, all our ministry did was attack people one by one.”

“I agree,” said Zhou.

After regaining his freedom, Lu regretted his mistakes. “Many people had beenwronged,” he said, “It takes 10 or 20 years to foster talent. But to ruin a person, it only takes one or two days, or one or two hours.”

Because the CCP promotes class struggle and hatred, one of its common tactics is to pick a group of citizens and label them as “enemies of the state.” After it got done persecuting this group, it would pick another group and attack them. After waves and waves of campaigns just like this, almost all Chinese citizens were trained to follow the Party line unconditionally. During this process, many aggressors have also become victims, just like ordinary citizens.

The Tragedy of a Model Police Chief

Ren Changxia, 40, was a former police chief in Dengfeng City, Henan Province. When she was returning from Zhengzhou to Dengfeng on April 14, 2004, the car she riding in had a collision with a large truck. Everyone else in the vehicle was all right, except for Ren, who died on site—despite having been seated in the safest place inside the vehicle.

Her eyes were closed for three days after her death. Many local residents believed that this was because people who had been wronged by her were seeking karmic retribution from her.

This incident also became a topic of discussion among police officers within the city, many who believe that this was a consequence of her carrying out the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners.

“I have heard about ‘Good is rewarded with good and evil meets with evil’,” Ren's sisters said, “I believe it now.”

After her death, the Public Security Ministry eulogized her and produced a 21-episode television series based on her life.

“By distorting Ren’s story as propaganda to deceive more people, the CCP has only added to the family's sins,” said a local resident.

On October 29, 2008, Ren’s husband Wei Chunxiao died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 45. They left one child behind.

“It's sad that people who follow the CCP are not only harming themselves, but also their family members,” said another local resident.

Even high officials could not escape the consequences of their actions. Sun Lijun, the former minister of the Public Security Ministry, was once responsible for handling major economic cases. He controlled the CCP's surveillance network and big data, and led the enactment of its draconian monitoring program. In early 2020, however, Sun was removed from office and investigated.

Looking back in history, from Nazi Germany to the Soviet Union, people who were involved in crimes against humanity have always met their just ends, even decades later. Today, the CCP's persecution of Falun Gong practitioners who follow Truthfulness-Compassion-Forbearance is one such crime—and only the latest in a long chain of the CCP's bloody campaigns since the 1940s.

To ensure a safe future and a clean conscience, it's best to acknowledge the crimes of this regime and distance oneself from it.

Wu Ziyou, a police officer, said he had unfortunately become a cog within the CCP’s apparatus of brutality.

“I look forward to freedom, but my work life has held me hostage,” he wrote in a statement to quit the CCP, “Without freedom, even my breathing is heavy.”

“Using the Chinese people as an excuse, this [CCP] regime has committed countless crimes against Chinese people. That is why I want to tell those who are still deceived and suppressed by the CCP to please step forward and say no to the regime!”

A parade outside China calling people to reject the CCP. The banner reads, “Quitting the Party will save ourselves.”

A parade outside China calling people to reject the CCP. The banner reads, “Quitting the Party will save ourselves.”

All articles, graphics, and content published on Minghui.org are copyrighted. Non-commercial reproduction is allowed but requires attribution with the article title and a link to the original article.

Category: Perspective