(Minghui.org) We can learn a lot from the past when looking back in history. One example is the suppression of Christians and the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Nero and Autumn Plague

According to historical records, the first imperially supervised persecution of Christians began with Nero (37-68). After becoming emperor in AD 54, Nero killed his mother Agrippina, brother Britannicus, and two wives, Claudia Octavia and Poppaea Sabina.

The Great Fire of Rome erupted on July 18, AD 64 and burned for over a week. Many ancient accounts claimed that it was Nero's plot to start the fire to destroy everything so he could implement his new urban development plan. He then blamed Christians for the arson, labeling them an anti-society sect. He also mobilized the Roman public to persecute Christians. As a result, some Christians were killed, torn apart by beasts, and burned alive as human torches.

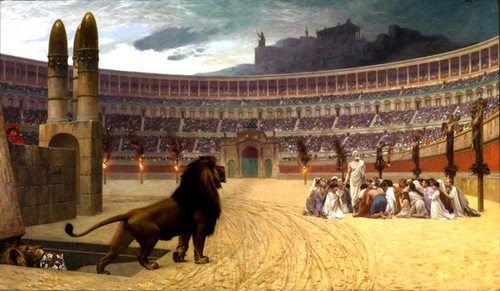

The Christian Martyrs Last Prayer by Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904) depicted a scene of Christian suppression in the Roman Empire: Christians were burned alive in the left, crucified on the right, and their last prayer.

The Christian Martyrs Last Prayer by Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904) depicted a scene of Christian suppression in the Roman Empire: Christians were burned alive in the left, crucified on the right, and their last prayer.

The Romans who believed in Nero and persecuted Christians soon received retribution. A plague broke out the following autumn in Rome and killed 30,000. Three years later, a rebellion against Nero took place. He fled Rome in AD 68 and died, possibly by suicide.

The chaos continued. With four emperors ruling in succession in AD 69, it was referred to as The Year of the Four Emperors by historians. In the next 300 years or so, however, Roman emperors did not learn the lesson, and instead continued the persecution, which brought further consequences.

The Antonine Plague

After Marcus Aurelius (121-180) became the Roman emperor in 161, he went a step further than any of his predecessors in persecuting Christians. According to some historians, “Christians were arrested, tried in the forum, and subsequently imprisoned. They were condemned to various punishments, including being fed to the beasts, torture, and the poor living conditions of imprisonment. Slaves belonging to Christians testified that their masters participated in incest and cannibalism.” As a result, Christians were executed or torn apart by beasts in the Colosseum.

The Antonine Plague broke out in 165 and lasted for 16 years with a horrific scene, “As the strength of the body is dissolved, the bowels dissipate in a flow; a fire that begins in the inmost depths burns up into wounds in the throat... the intestines are shaken with continuous vomiting ... the eyes are set on fire from the force of the blood ... as weakness prevails through the failures and losses of the bodies, the gait is crippled or the hearing is blocked or the vision is blinded ...”

During the plague, there were up to 2,000 deaths a day in Rome, and with a mortality rate of about 25%, the total deaths was estimated at five million. The disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas, and weakened the Roman army, ending a relatively peaceful period of Roman history.

Plague of Cyprian

The Plague of Cyprian started in 250 and ended in 270. During peak time, it killed as many as 5,000 people per day in Rome. It caused widespread manpower shortages for food production and the Roman army, severely weakening the empire during the Crisis of the Third Century. Agents of the plague were suspected to include smallpox, pandemic influenza, and viral hemorrhagic fever (filoviruses) like the Ebola virus.

This epidemic occurred one year after Trajan Decius became emperor in 249. He issued an order demanding everyone in the Empire (except Jews, who were exempted) to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods. The sacrifices had to be performed in the presence of a Roman magistrate, and be confirmed by a signed and witnessed certificate from the magistrate. A large number of Christians were killed for not giving up their belief.

Two years into his reign, Decius died in a battle in 251. Nineteen years later, then Roman emperor Claudius Gothicus also died in the plague.

During the plague, Christians played an active role in caring for the ill as well as actively providing care in the burial of the dead. In the end, the plague not only strengthened but helped to spread Christianity throughout the the empire.

Diocletianic Persecution

After Diocletian (244-311) became emperor in 284, he was relatively tolerant of Christians in the early years. Following advice from his son-in-law Galerius, however, Diocletian started a persecution in February 303. He gave orders to destroy Christian churches, burn scriptures, and seize properties. He purged Christians from both the military and government, and subjected them to detention and even execution. Known as Diocletianic or Great Persecution, it was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire.

By then, Christians had already been accepted by many people, including Diocletian’s wife and some senior officials. Diocletian resigned in 305 for health reasons and Galerius continued the persecution policy.

Galerius was later bedridden with gruesome diseases. “His disease was occasioned by a very painful lingering disorder. His body, swelled by an intemperate course of life to an unwieldy corpulence, was covered with ulcers, and devoured by innumerable swarms of those insects who have given the name to a most loathsome disease,” wrote historian Edward Gibbon.

Regretting over his wrongdoing, Galerius issued an order in April 311 to officially end the persecution.

After Constantine the Great was in reign, he believed in Christians and issued Edict of Milan in 313, which further declared religious tolerance for Christianity in the Roman empire.

The sins committed during religious belief were devastating. It was estimated that about 60 million people died during the plagues, followed by the downfall of the Roman Empire.